Curating Women's International Thought

Katharina Rietzler and Joanna Wood

Much of the work on the Leverhulme Research Project has involved locating, recovering and selecting women’s writing on international relations in the American and British empires in the early and mid-twentieth century. As an exercise, curating, the practice of selecting and ordering involves recognizing patterns in a wealth of material, and presenting the material accordingly. This practice is not neutral. As a group of researchers, we have spent much time reflecting on the mechanisms and criteria of inclusion and exclusion, both in the past and the present day. The results of these reflections so far can be found in our list of publications but we know that much work remains to be done.

One aspect of that work is reaching out to a broader audience. Coinciding with our capstone conference in May 2022, the core WHIT project team, made up of Patricia Owens, Katharina Rietzler, Kimberly Hutchings and Joanna Wood, have curated a public exhibition at the London School of Economics (LSE), to run from 5 May to 2 September 2022. This has involved working with library and museum professionals, curators and mount makers, and thinking about women international thinkers in a way that was new for us. Exhibitions tend to emphasise visual materials and objects rather than the written word. Room for analysis and exposition is limited and the space of the exhibition itself becomes part of the message. In many ways, it is the opposite of the traditional academic approach. It moves us from reading to seeing and grants far more interpretive power to the visitor.

The exhibition form also opens up access for many people excluded from traditional academic outputs, such as those who are visual learners, neurodivergent, have English as an additional language, or have learning needs or disabilities. However, it can also exclude, as Joanna, our PhD student who is visually impaired, knows well. Committing to making the exhibition accessible to blind and visually impaired audiences, as well as recognising the gains for other groups, gave us the chance to think about the themes of inclusion and representation in a new light - this time focused on diverse audiences and curators, as well as historical producers of knowledge.

Historical documents and old books on two opposite shelves in the LSE basement

The curating process began more than a year before the event itself, in spring 2021. We drew up shortlists of objects and images, structured into thematic clusters that would fit the exhibition space. Physical copies of hardcover editions and historical photographs had to be procured, and image rights secured. We were all novices: it took time to fully understand the nature of the varied spaces and mediums available, including digital video screens and non-digital display cases, and how to make the most of them. We were lucky to be able to rely on both the LSE’s library and museum professionals and the treasure troves of the LSE’s archives and special collections. Over several meetings in the cavernous basement of the Library building, we were able to retrieve rare photographs of women thinkers, pamphlets that are hard to find anywhere else in the United Kingdom or indeed in Europe, archival material including correspondence and newspaper clippings, and rare editions of books and reports.

Archival boxes stacked in two floor to ceiling shelves in the LSE basement

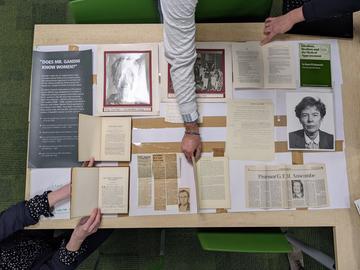

One of our most enjoyable meetings involved creating the ‘mock-ups’ for our physical table-tops and plinths. We were forced to really reflect on how to arrange materials in a way that told a story in three dimensions and was aesthetically and intellectually appealing. For example, for the table-top on political interventions, we decided to group thinkers together by political persuasion, with communist revolutionaries on the left, liberals in the middle and conservatives and neo-conservatives on the right. Such identifications are, of course, imperfect, but these are nuances that visitors can further explore themselves, hopefully by delving into the work written by women thinkers or our own academic outputs. The images included in this post give a sense of the process.

Exhibition objects and mock-up captions laid out on a table

Much of this work was highly visual, in a way that for Jo, and other blind or visually impaired people, cannot be bridged by assistive technology alone. Access came through the rest of the team and the LSE staff describing what was happening as we went along, the items under consideration, their layout, the exhibition space, and colour schemes. Being descriptive actively enhanced our work: you don’t really understand something or why it is important until you have had to describe it. It got us thinking about why we were drawn to certain exhibits, where their power lay and what representation meant in different contexts. To make the exhibition accessible, we created an audio-described guide to be hosted on the LSE website. From the opening poster to the closing plinth, each of us describes the contents of the exhibition, as well as the way in which objects and images are arranged in space. Historian and Merze Tate biographer, Barbara D. Savage, kindly recorded a two-minute audio-visual of the main exhibition poster, which centres on an image of Merze Tate.

Capturing a visual object in words is harder than it sounds - it’s certainly an art more than a science. For an exhibition like this, rather than say for Jo’s PhD research, it is not possible to describe every detail. The key is to identify what makes the item important and describe this whilst also capturing the overall aesthetic or ‘visual punch’ that a non-blind visitor gets when they view it. It also allowed us a little more ‘text’! Each of us recorded our descriptions on phones and then emailed these to be uploaded on the exhibition website. We were struck by how easy, quick and no-cost it was to provide such fundamental access, and yet how infrequent this remains in academia. We also realised how useful a described guide was for anyone: it helps you focus on the key aspects of an exhibit, makes it easy to engage with the curator’s perspective and enhances your experience by making the experience multi-sensory. This is the ‘blindness gain’ identified and theorised by Hannah Thompson.[1]

Working both visually and descriptively prompted us to reflect more carefully on barriers to inclusion in academic research but also when it comes to disseminating academic outputs, a crucial requirement for funding bodies. These are reflections that will carry into our work and outputs going forwards. In our case, we were lucky to be able to draw on the expertise and personal experience in our team but what we did is replicable by anybody, at no cost. Even without the access, and the equality this brings, the reflexive insights make the descriptive process worthwhile. It is an extra, under-used analytical tool we can all benefit from. Preparing the exhibition has been an exciting, novel and transformative experience. We would really encourage others to think about exhibition-style outputs in their research and hope that by showing how easy it is to provide description for visual content, others will follow suit and academia will become more accessible. But, most importantly, every member of our team will get to enjoy the exhibition that represents the culmination of the project. We look forward to describing that photo!